Janette Laverrière (*1909, †2011)

For more on Janette Laverrière's life and work, please see Janette Laverrière by Yves Badetz, available at Norma Editions.

The Swiss-French interior designer, artist, and political activist Janette Laverrière was a prominent member of the Modernist design scene in postwar France. Through her long and varied practice, Laverrière mastered the interplay between the contrasting styles of Modernism and Art Deco in over 1,500 designs. Her idiosyncratic work slides between art and design and combines elegant features, political metaphors, unorthodox materials, and surrealistic forms. After more than a century of life, Laverrière left behind an eclectic oeuvre of whimsical furniture, auratic installations, and her Evocations, a complex series of sculptural mirror objects with an eccentric twist. While decidedly twentieth-century, Laverrière’s body of work appears contemporary today, and can increasingly be seen in international art exhibitions, design fairs, and the homes of connoisseurs.

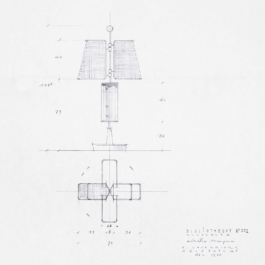

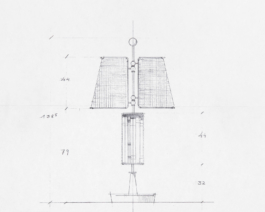

Technical drawing of Bibliotheque Tournante, ca. 1950

⟵ Janette Laverrière, ca. 1950

Born in 1909 to the distinguished Swiss architect Alphonse Laverrière and a South African-Jewish mother, Laverrière was exposed early on to the clash between the opulence of Art Deco and the austerity of early Modernist architecture that surrounded her father’s practice. After studying interior architecture and design at the Allgemeine Gewerbeschule in Basel, she briefly apprenticed at her father’s firm before moving on to the atelier of Jacques-Émile Ruhlmann, a master craftsman known for building glamorous Art Deco furniture for the French elite. There, Laverrière took in the elegance of proportion and learned to draw a curve with a single flick of her wrist. The luxuriousness of form and material Ruhlmann used was a stark contrast from what Laverrière absorbed at the iconic Bauhaus, where she took classes in geometry and embroidery.

In the mid-1930s, Laverrière left Ruhlmann’s atelier and started to collaborate with her first husband, Maurice Pré, whom she met at Ruhlmann’s. Together with her husband, she garnered her first recognition in the international design arena, earning several commissions for home interiors. Under the alias M. J. Pré, they received major awards at the annual exhibitions of the Salon des artistes décorateurs, culminating in a gold medal in 1937. Their collaboration ended with the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939. Laverrière earned a state commission and was sent to southern France, where she designed camouflage for factories. This experience deeply sharpened her political eye, opening her up to the Resistance and Front National. Toward the end of the war, she joined the Communist Party and formed the Front National des Décorateurs, an organization exclusively for artists who had been members of the Resistance.

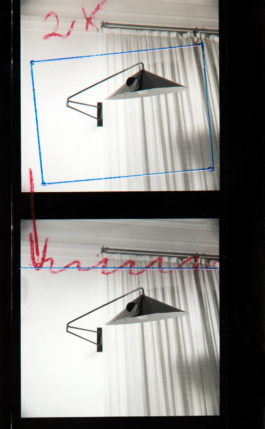

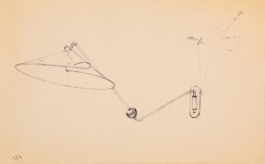

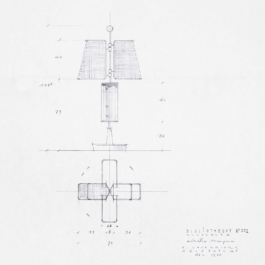

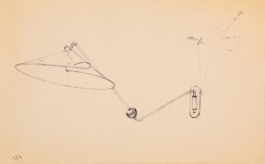

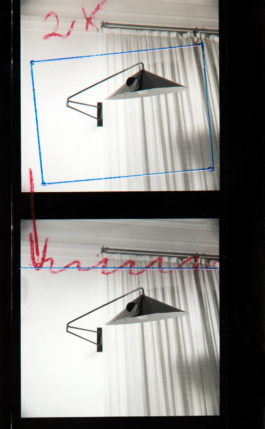

Technical drawing of Chapeau Chinois II, ca. 1952

⟵ Historic photograph of Chapeau Chinois I, ca. 1952

As Laverrière grew more politically active through the 1940s, both her lifestyle and designs grew increasingly feminist in nature. After the war, she and Pré divorced, and works like her Kitchen for the 50s expressly sought to unshackle housewives from their traditional places in the home and society. The kitchen included the Vege-Table, a chopping board on wheels that would allow housewives to follow conversation through different rooms of the home while still cooking. ("Today," Laverrière said in 2009, "I’d probably put wheels under the husband instead!")

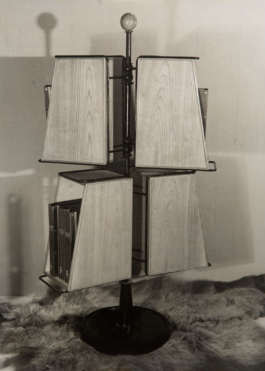

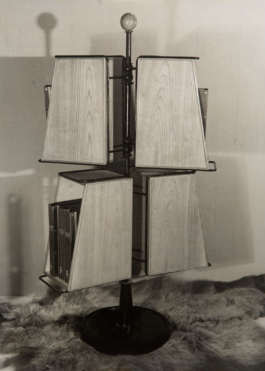

In the 1950s, Laverrière was at her most prolific. She created the rotating cherry-wood Bibliothèque Tournante, a movable bookshelf that, rather than stand silent against the wall, would be a conversation piece that easily and quickly reorients to suit the needs or whims of its users. Soon after, she designed her egg-shaped table Oeuf with adjustable legs so that it could transform from dining to coffee table in one motion, displaying Laverrière’s awareness of the changing tempo of the modern home. Her idiosyncratic response to the zeitgeist and interplay between the contrasting styles of Modernism and Art Deco is mastered in her hand-wrought metal lamps Chapeau Chinois I and II. Here she combined adaptable functionality and Modernist materials with a whimsical bend echoing Art Deco elegance.

Technical drawing of Bibliothèque Tournante, ca. 1950

⟵ Historical photograph of Bibliothèque Tournante, ca. 1950

During this time, a prestigious commission from the Mobilier National — an esteemed state furniture archive where ministers and embassy officials would choose their office decor — opened new doors for Laverrière. She was asked to design an interior for an ambassador along with a few tables for the Palais de l’Élysée. While at work, Laverrière suggested a study for the ambassador’s wife, who continued her husband’s work in his absence. The result, Cabinet de Travail d’une Femme d’Ambassadeur, featured a winged desk in rosewood with secret compartments for private letters, at once a luxury object and an emancipatory statement for a high-society 1950s woman.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Laverrière passed on her profound knowledge and distinguished craftsmanship to the next design generation, teaching interior and furniture design at the École Camondo in Paris. This was also the time when Laverrière ran a gallery in Paris to exhibit her work and that of her friends and, notably, when she accomplished two of her most significant design projects. For the first, she was invited by the president of a newly independent Niger, Hamani Diori, to create a vast array of furniture for the interior of the presidential palace in Niamey. Her unorthodox materials and modern designs, such as the use of enameled iron and visible plywood edges narrated distance from Niger's colonial past. Further, the design prominently featured yellow, the color of the independence movement. Later, Laverrière was asked to interior the Swiss Hospital at Issy-les-Moulineaux, launching a project that called on her understanding of functional design and of color schemes.

Evocations: La Commune, 2001

at Silberkuppe, Berlin

⟵ Evocations: Freedom, 2010

at Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

Evocations: Victor Hugo, 2001

at Walker Art Center, Minneapolis ⟶

In the late 1980s, after more than five productive decades, Laverrière stopped accepting any more design commissions. Instead, she started to work on highly complex objects based on personal interests, political allegories, surrealistic shapes, and poetical narratives. Her Evocations, a series of sculptural, convex and concave mirror objects begun in 1989 followed a new credo that would guide her for the rest of her life: "It’s useful to have useless things." One prominent piece of her Evocations is La Commune, Hommage à Louise Michel, which Laverrière designed in 2001 commemorating the writer, activist, and leader of the 1871 Paris Commune, Louise Michel. Mounted on a bright red background, it is embedded in a rosewood box and covered by a metal lid riddled with bullet holes, a collision of material by which Laverrière mirrored the brutality of the riots. This unorthodox idiom led to an artistic dialogue with the artist Nairy Baghramian, who was drawn to Laverrière for both her political convictions and the unapologetic confidence of her craftsmanship.

Janette Laverrière, ca. 2008

⟵ Nairy Baghramian and Janette Laverrière, ca. 2008

In 2008, Laverrière and Baghramian collaborated for the first time. Baghramian had been invited by the curators of the 5th Berlin Biennale, Adam Szymczyk and Elena Filipovic, to work with another artist on a project for the Schinkel Pavilion in Berlin. Together, Laverrière and Baghramian created a pavilion within the pavilion titled after Laverrière’s late Parisian gallery La Lampe dans l’Horloge, itself named from a story by one of Laverrière‘s favorite poets, André Breton. Their installation featured bold, colored panels, the Bibliothèque Tournante, and ten sculptural mirror objects.

La Lampe dans l'Horloge

at Schinkel Pavillon, Berlin

⟵ La Lampe dans l'Horloge

at Schinkel Pavillon, Berlin

La Lampe dans l'Horloge

at Walker Art Center, Minneapolis ⟶

Laverrière applied her artistic practice on a larger scale at the Kunsthalle Baden-Baden in 2009, where, together with Baghramian, she reconstructed her Entre Deux Actes — Loge de Comédienne, the imagined dressing room of an actress, which first debuted at the Salon in 1947. This auratic interior, sitting intentionally on the cusp of art and design, made room for Laverrière and Baghramian to contextualize it into the complex spheres of contemporary art.

Historic photograph of Entre Deux Actes, ca. 1947

⟵ Entre Deux Actes

at Kunsthalle Baden-Baden

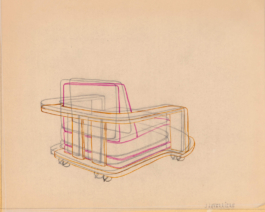

Thereafter Laverrière was posthumously received as more than an interior designer. As her oeuvre reenters the canon, Laverrière is increasingly understood as an artist. Her work is featured in the prestigious collections of the Mobilier National, the Musée d’Art Moderne, and the Centre Pompidou. Late in life, Laverrière arranged to spread her work throughout the world, granting exclusive production licenses to the director of JL Editions. These exclusive JL Editions include the Bibliothèque Tournante, the Chapeau Chinois I and II, and her very last furniture design Fauteuil Cognac, an updated version of her 1967 Whiskey Chair. Laverrière redesigned this imposing armchair exclusively for an exhibition in 2014 at the Berlin art gallery Silberkuppe.

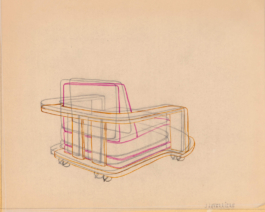

Technical drawing of Fauteuil Cognac, ca. 2010

⟵ Historic photograph of Whiskey Chair, ca. 1967

Fauteuil Cognac, 2010

at Silberkuppe, Berlin ⟶

Toward the end of her life, Laverrière referred to her friend and collaborator Nairy Baghramian as "sisters in creation," — as if not generationally separated, but of the same era. Indeed, Laverrière herself, alongside her artistic output, seemed to defy time. She appropriated materials, colors, epochs, and rules of design, building a multifaceted oeuvre that spread wide across the early 20th century. Her immense hunger for knowledge led her to challenge herself continually through a century of life, ultimately making her a unique position in art and design history. Laverrière leaves behind a vast range of intricate cultural wonders that aesthetically and conceptually revise history, making room for a figure as complex as this designer turned artist, Communist, divorcée, and devoted feminist.

Janette Laverrière (*1909, †2011)

For more on Janette Laverrière's life and work, please see Janette Laverrière by Yves Badetz, available at Norma Editions.

Janette Laverrière, ca. 1950

The Swiss-French interior designer, artist, and political activist Janette Laverrière was a prominent member of the Modernist design scene in postwar France. Through her long and varied practice, Laverrière mastered the interplay between the contrasting styles of Modernism and Art Deco in over 1,500 designs. Her idiosyncratic work slides between art and design and combines elegant features, political metaphors, unorthodox materials, and surrealistic forms. After more than a century of life, Laverrière left behind an eclectic oeuvre of whimsical furniture, auratic installations, and her Evocations, a complex series of sculptural mirror objects with an eccentric twist. While decidedly twentieth-century, Laverrière’s body of work appears contemporary today, and can increasingly be seen in international art exhibitions, design fairs, and the homes of connoisseurs.

Technical drawing of Bibliotheque Tournante, ca. 1950

Born in 1909 to the distinguished Swiss architect Alphonse Laverrière and a South African-Jewish mother, Laverrière was exposed early on to the clash between the opulence of Art Deco and the austerity of early Modernist architecture that surrounded her father’s practice. After studying interior architecture and design at the Allgemeine Gewerbeschule in Basel, she briefly apprenticed at her father’s firm before moving on to the atelier of Jacques-Émile Ruhlmann, a master craftsman known for building glamorous Art Deco furniture for the French elite. There, Laverrière took in the elegance of proportion and learned to draw a curve with a single flick of her wrist. The luxuriousness of form and material Ruhlmann used was a stark contrast from what Laverrière absorbed at the iconic Bauhaus, where she took classes in geometry and embroidery.

In the mid-1930s, Laverrière left Ruhlmann’s atelier and started to collaborate with her first husband, Maurice Pré, whom she met at Ruhlmann’s. Together with her husband, she garnered her first recognition in the international design arena, earning several commissions for home interiors. Under the alias M. J. Pré, they received major awards at the annual exhibitions of the Salon des artistes décorateurs, culminating in a gold medal in 1937. Their collaboration ended with the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939. Laverrière earned a state commission and was sent to southern France, where she designed camouflage for factories. This experience deeply sharpened her political eye, opening her up to the Resistance and Front National. Toward the end of the war, she joined the Communist Party and formed the Front National des Décorateurs, an organization exclusively for artists who had been members of the Resistance.

Technical drawing of Chapeau Chinois II, ca. 1952

Historic photograph of Chapeau Chinois I, ca. 1952

As Laverrière grew more politically active through the 1940s, both her lifestyle and designs grew increasingly feminist in nature. After the war, she and Pré divorced, and works like her Kitchen for the 50s expressly sought to unshackle housewives from their traditional places in the home and society. The kitchen included the Vege-Table, a chopping board on wheels that would allow housewives to follow conversation through different rooms of the home while still cooking. ("Today," Laverrière said in 2009, "I’d probably put wheels under the husband instead!")

In the 1950s, Laverrière was at her most prolific. She created the rotating cherry-wood Bibliothèque Tournante, a movable bookshelf that, rather than stand silent against the wall, would be a conversation piece that easily and quickly reorients to suit the needs or whims of its users. Soon after, she designed her egg-shaped table Oeuf with adjustable legs so that it could transform from dining to coffee table in one motion, displaying Laverrière’s awareness of the changing tempo of the modern home. Her idiosyncratic response to the zeitgeist and interplay between the contrasting styles of Modernism and Art Deco is mastered in her hand-wrought metal lamps Chapeau Chinois I and II. Here she combined adaptable functionality and Modernist materials with a whimsical bend echoing Art Deco elegance.

Historical photograph of Bibliothèque Tournante, ca. 1950

During this time, a prestigious commission from the Mobilier National — an esteemed state furniture archive where ministers and embassy officials would choose their office decor — opened new doors for Laverrière. She was asked to design an interior for an ambassador along with a few tables for the Palais de l’Élysée. While at work, Laverrière suggested a study for the ambassador’s wife, who continued her husband’s work in his absence. The result, Cabinet de Travail d’une Femme d’Ambassadeur, featured a winged desk in rosewood with secret compartments for private letters, at once a luxury object and an emancipatory statement for a high-society 1950s woman.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Laverrière passed on her profound knowledge and distinguished craftsmanship to the next design generation, teaching interior and furniture design at the École Camondo in Paris. This was also the time when Laverrière ran a gallery in Paris to exhibit her work and that of her friends and, notably, when she accomplished two of her most significant design projects. For the first, she was invited by the president of a newly independent Niger, Hamani Diori, to create a vast array of furniture for the interior of the presidential palace in Niamey. Her unorthodox materials and modern designs, such as the use of enameled iron and visible plywood edges narrated distance from Niger's colonial past. Further, the design prominently featured yellow, the color of the independence movement. Later, Laverrière was asked to interior the Swiss Hospital at Issy-les-Moulineaux, launching a project that called on her understanding of functional design and of color schemes.

Evocations: Freedom, 2010

at Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

Evocations: La Commune, 2001

at Silberkuppe, Berlin

Evocations: Victor Hugo, 2001

at Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

In the late 1980s, after more than five productive decades, Laverrière stopped accepting any more design commissions. Instead, she started to work on highly complex objects based on personal interests, political allegories, surrealistic shapes, and poetical narratives. Her Evocations, a series of sculptural, convex and concave mirror objects begun in 1989 followed a new credo that would guide her for the rest of her life: "It’s useful to have useless things." One prominent piece of her Evocations is La Commune, Hommage à Louise Michel, which Laverrière designed in 2001 commemorating the writer, activist, and leader of the 1871 Paris Commune, Louise Michel. Mounted on a bright red background, it is embedded in a rosewood box and covered by a metal lid riddled with bullet holes, a collision of material by which Laverrière mirrored the brutality of the riots. This unorthodox idiom led to an artistic dialogue with the artist Nairy Baghramian, who was drawn to Laverrière for both her political convictions and the unapologetic confidence of her craftsmanship.

Nairy Baghramian and Janette Laverrière, ca. 2008

In 2008, Laverrière and Baghramian collaborated for the first time. Baghramian had been invited by the curators of the 5th Berlin Biennale, Adam Szymczyk and Elena Filipovic, to work with another artist on a project for the Schinkel Pavilion in Berlin. Together, Laverrière and Baghramian created a pavilion within the pavilion titled after Laverrière’s late Parisian gallery La Lampe dans l’Horloge, itself named from a story by one of Laverrière‘s favorite poets, André Breton. Their installation featured bold, colored panels, the Bibliothèque Tournante, and ten sculptural mirror objects.

La Lampe dans l'Horloge

at Schinkel Pavillon, Berlin

La Lampe dans l'Horloge

at Schinkel Pavillon, Berlin

La Lampe dans l'Horloge

at Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

Laverrière applied her artistic practice on a larger scale at the Kunsthalle Baden-Baden in 2009, where, together with Baghramian, she reconstructed her Entre Deux Actes — Loge de Comédienne, the imagined dressing room of an actress, which first debuted at the Salon in 1947. This auratic interior, sitting intentionally on the cusp of art and design, made room for Laverrière and Baghramian to contextualize it into the complex spheres of contemporary art.

Entre Deux Actes

at Kunsthalle Baden-Baden

Historic photograph of Entre Deux Actes, ca. 1947

Thereafter Laverrière was posthumously received as more than an interior designer. As her oeuvre reenters the canon, Laverrière is increasingly understood as an artist. Her work is featured in the prestigious collections of the Mobilier National, the Musée d’Art Moderne, and the Centre Pompidou. Late in life, Laverrière arranged to spread her work throughout the world, granting exclusive production licenses to the director of JL Editions. These exclusive JL Editions include the Bibliothèque Tournante, the Chapeau Chinois I and II, and her very last furniture design Fauteuil Cognac, an updated version of her 1967 Whiskey Chair. Laverrière redesigned this imposing armchair exclusively for an exhibition in 2014 at the Berlin art gallery Silberkuppe.

Historic photograph of Whiskey Chair, ca. 1967

Technical drawing of Fauteuil Cognac, ca. 2010

Fauteuil Cognac, 2010

at Silberkuppe, Berlin

Toward the end of her life, Laverrière referred to her friend and collaborator Nairy Baghramian as "sisters in creation," — as if not generationally separated, but of the same era. Indeed, Laverrière herself, alongside her artistic output, seemed to defy time. She appropriated materials, colors, epochs, and rules of design, building a multifaceted oeuvre that spread wide across the early 20th century. Her immense hunger for knowledge led her to challenge herself continually through a century of life, ultimately making her a unique position in art and design history. Laverrière leaves behind a vast range of intricate cultural wonders that aesthetically and conceptually revise history, making room for a figure as complex as this designer turned artist, Communist, divorcée, and devoted feminist.

JL Editions

Marienstraße 28

10117 Berlin, Germany

For inquiries please contact

Michel Ziegler

mz@janettelaverriere.com

+49 (0)178 — 45 42 911

JL Editions is the official and authorized manufacturer of select designs by the Janette Laverrière estate.

All objects are hand manufactured by expert craftspeople in Germany under supervision and quality control of JL Editions.

© JL Editions, Berlin

JL Editions

Marienstraße 28

10117 Berlin

Germany

For inquiries please contact

Michel Ziegler

mz@janettelaverriere.com

+49 (0)178 — 45 42 911

JL Editions is the official and authorized manufacturer of select designs by the Janette Laverrière estate.

All objects are hand manufactured by expert craftspeople in Germany under supervision and quality control of JL Editions.

© JL Editions, Berlin